05/02/2011 | 01:46 PM

A clear, working system – with specific procedures and dedicated staff personnel – triggers quick, correct, and complete action by some government agencies on access to information requests.

But the absence of such a system in most other agencies, as well as the lack of fully defined rules and procedures that all agencies must observe in responding to requests, remain barriers to access.

The bad results: inordinate delays, token compliance with lawful deadlines, disregard for the Constitution’s guarantees of the public’s right to know, and a general slide to secrecy, not transparency, in most of the bureaucracy under the Aquino administration.

For instance, requests for copies of the Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) that the PCIJ filed with the secretaries of Finance and Interior and Local Government drew quick and correct action.

The requests were forwarded promptly to the departments’ respective personnel units that had copies of the documents. The personnel units approved the requests like these were regular office transactions. Ahead of the 10 working days’ deadline in the law for agencies to act on SALN requests, the two institutions got the work done.

In contrast, most other agencies moved exceedingly slow on similar requests, flipped and tossed the requests to other agencies, or simply ignored and rebuffed the requests outright.

The Office of the President and the Ombudsman are the stellar examples of restrictive, inefficient access to information regimes in place today.

Yet another is the Philippine National Police. Over the last three months since Feb. 18, the PNP has passed around the PCIJ’s request for SALNs to at least five PNP units: from the office of the PNP director-general to the office of the PNP Internal Affairs Service, to the office of the PNP Chief of the Directorial Staff, to the PNP Public Information Office (PIO), and finally, to the PNP Directorate for Personnel and Records Management (DPRM).

Three months and five offices later, the PNP has yet to provide the PCIJ a single page of a single SALN that any of its top cops had filed.

On Apr. 26, or 10 weeks after the PCIJ request was filed, the PNP’s PIO told PCIJ that the request should be sent to the PNP-DPRM, where a staff personnel told the PCIJ that it is the PNP-PIO that should decide on the matter. The PNP-DPRM staff said the information enrolled in the SALNs are “sensitive." The employee later advised to the PCIJ to write another letter addressed to the PNP chief, with a note of attention to the DPRM head.

Multiple layers of bureaucracy, buck-passing, inordinate delays, and seeming indifference to or ignorance of the relevant laws on the part of some agencies – all these barriers are sure to test the patience and stamina of those filing requests for access to SALNs and other documents.

This was the situation in the House of Representatives for three years’ running under Speaker Prospero Nograles Jr. of the 14th Congress, which lingers in part to this day under Speaker Feliciano Belmonte Jr. of the 15th Congress.

The PCIJ’s request for the SALNs of House members made the rounds and went back and forth in multiple office units of the chamber – the office of the Secretary-General, which forwarded the request to the House Legal Division and to the offices of all the members of the House.

The Legal Division later sent back the PCIJ request to the Secretary General for her approval. After this was granted, the Secretary General’s Office moved a transmittal letter with its stamp of approval to the House Records Division.

But the run-around did not stop there. Follow-up calls had to be made with the House Records Office before it finally acknowledged the Secretary General’s approval and actually allowed the release of the SALNs for reproduction.

This resort to red tape also marked the action of the Office of the Ombudsman to similar requests that the PCIJ had separately filed with the nation’s top integrity agency. Under just-resigned Ombudsman Ma. Merceditas N. Gutierrez, the agency had reverted to old, restrictive procedures in dealing with requests for SALNs.

The requests filed with Gutierrez’s office were referred first to the Office of Legal Affairs so it could study and recommend action on the same. The catch was that the recommendations of the Office of Legal Affairs had to be sent back to Gutierrez for her final approval.

Despite these restrictive and redundant procedures, however, the PCIJ encountered some officials who demonstrated exemplary openness and respect for the public’s right to know.

This honorable roster includes Commission on Elections (Comelec) Commissioner Rene V. Sarmiento and three House members: Batanes Rep. Henedina R. Abad, Lanao del Sur Rep. Mohammed Hussein P. Pangandaman, and Abante Mindanao Party-List Rep. Maximo B. Rodriguez Jr. Without any need for prodding, all four, on their own volition, gave the PCIJ copies of their SALNs via fax or mail. They did so even while their agencies, the Comelec and the House, had yet to act fully on the PCIJ’s requests for SALNs.

In the case of the Armed Forces and some executive departments, avoidance of action and retreat to higher ground or superior agencies defined the token action that agencies made on the PCIJ’s requests for SALNs. Their usual resort was to refer the requests to either the Office of the President, the Civil Service Commission, or the Ombudsman.

But while some agencies are secretive about the SALNs of their top officials, they are also more open to granting requests for other documents that they hold in custody.

The Comelec generously shared documents on the election spending reports filed by candidates in the May 2010 elections, the Department of Social Welfare and Development and the Department of Budget and Management documents on the Conditional Cash Transfer Program, the Sandiganbayan databases on the status of graft and corruption cases filed before its courts, and the Securities and Exchange Commission and Department of Trade and Industry on certificates of registration of business entities.

Amid these hopeful signs of openness though are hints of mistrust, indifference to transparency laws, or even contempt toward people seeking access to information that some civil servants apparently harbor still.

In exchanges with the PCIJ staff, some have made side comments that disclosing the SALNs may pose “security risks" for their officials, that the documents may only be released through a court order, or that the documents supposedly contain “confidential" information. – Karol Anne M. Ilagan, PCIJ, May 2011

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

PCIJ: President’s office still 'secretive' under Aquino

ANDREO C. CALONZO, GMA News

05/02/2011 | 03:27 PMThe Office of the President remains to be "secretive" under the leadership of President Benigno Aquino III, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) said Monday.

PCIJ executive director Malou Mangahas said Aquino’s office has imposed barriers to free access of government records such as additional documentary requirements, despite the President’s transparency platform during his 2010 election campaign.

"The President has been an exemplar in filing complete and prompt reports… If the President could be this good, this should be the case in the entire bureaucracy," Mangahas said at a forum in Quezon City.

A PCIJ report said Aquino’s office demanded various documents such as registration records, mayor’s permit and an executive summary describing where the files would be used before giving out copies of statements of assets, liabilities and net worth (SALNs).

"Instead of taking the lead in pushing for transparency in government, the Office of the President seems to be following the footsteps of other state agencies that would rather keep documents close to their chests," the report said.

The PCIJ report added that three of the government’s "integrity" institutions — the Commission on Audit, the Commission on Elections and the Civil Service Commission — are among the "most secretive" agencies in the country.

The three agencies "restrict" access to public records such as SALNs and personal data sheets of government officials through various ways, ranging from imposing high prices for photocopying to sheer "ignorance" of the relevant laws on free access to information.

Mangahas said that one of the ways to address the continuing lack of access to information in the Aquino administration is the passage of the Freedom of Information (FOI) bill currently pending in Congress.

"The FOI bill is non-partisan and it protects the people most of all. Freedom of information is constitutionally mandated… Nananawagan kami sa Senado at sa House of Representatives na kung puwede ay balikan ang bill na ito," she said.

Two separate versions of the FOI bill, Senate Bill 11 and House Bill 53, are still pending at the committee level in both chambers of Congress.

Clear stand

Various members of civil society groups meanwhile urged Aquino to state a clear stand on the FOI bill.

Lawyer Nepomuceno Malaluan, co-director of the Institute for Freedom of Information, said the President should go beyond "undemocratic tendencies" and back the measure.

"We ask President Aquino to categorically state whether or not he supports the passage of the FOI act, and if so, when," he said during the same forum.

He added that his group has already sent a letter to Aquino’s office requesting a dialogue to convince the President to include the FOI bill in his priority measures.

During the presidential campaign, Aquino vowed to prioritize the FOI bill, but did not include the measure in his priority legislative agenda during the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council (LEDAC) meeting last February. [See: Palace: FOI bill may yet be prioritized later this year]

Transparency and Accountability Network (TAN) executive director Vincent Lazatin meanwhile said that Aquino should consider the FOI bill as a "central" tool for his anti-corruption agenda.

"Transparency and access to information can be Aquino’s most potent weapon against corruption and poverty," he said. — RSJ/HS, GMA News

A posse of Pantawids

Che de los Reyes, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

05/30/2011 | 10:42 AMTHE straight and narrow path, or “matuwid na daan" in Filipino, is where President Benigno Simeon ‘Noynoy’ C. Aquino III says he wishes all Filipinos would tread. And perhaps to prove that he’s not all talk and no action, Aquino has splurged billions of pesos on many “pantawid" (“tide over" in English) programs that all involve cash subsidies for the poor.

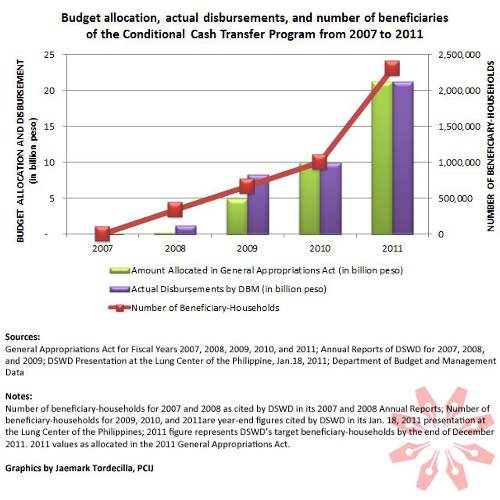

The biggest of these “pantawid" initiatives, of course, is the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) or the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) that has been allotted P21 billion in the 2011 General Appropriations Act (GAA), and a substantial part of it funded with loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Three other programs are also listed under the 4Ps, each with its own hefty budget: the “Supplemental Feeding Program" (P2.88 billion), “Food for Work for Internally Displaced Persons" (P881 million), and “Rice Subsidy Program" (P4.23 billion). Altogether, these other subsidy programs are worth an additional P8 billion.

In the CCT and these other programs, the 2,500-strong Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) has been designated lead agency, with other agencies as co-implementers or mere deputies. One can say that the DSWD suddenly has its plate full not just with too much work, but also too much money.

In fact, the P21 billion set aside for the CCT in the GAA this year is more than double the allocation that the DSWD received last year. It is also the largest cost item in the department’s budget, eating up 62 percent of the agency’s total allotment of P34.2 billion for 2011.

(To coincide with the recent observance of Labor Day, Aquino launched through Executive Order No. 32 the “Pantawid Pasada" or Public Transport Assistance Program. Under it, a targeted total of 214,596 jeepney and tricycle drivers and operators received “smart cards" pre-loaded with up to P1,050, or roughly a fuel assistance of P35 a day for one whole month. The program’s launch, which had energy department officials handing out cards to drivers who had queued for hours, cost taxpayers at least P225.32 million, net of administrative expenses. The implementing rules for EO No. 32 say that Pantawid Pasada has an initial allocation of P450 million.)

To be sure, cash grants to targeted beneficiaries have been acknowledged as better and less-costly safety net measures, in contrast to price subsidies that tend to benefit even the rich. It is not clear, however, how these cash-outs supplement each other, or what outcomes they are designed to yield, under the Philippine Development Plan for 2011-2016 that the government fully disclosed only last week.

It’s also unclear how a small executive agency like the DSWD will be able to implement these programs efficiently, without sacrificing its regular tasks under its “social welfare arm" – providing assistance to victims of abuse and exploitation, and relief assistance in times of disasters. DSWD Secretary Corazon ‘Dinky’ Soliman herself says these tasks should go hand-in-hand with the agency’s “development arm" that includes implementing the CCT.

At the very least, the DSWD likes to say that the pantawid programs complement its work. It also bristles at any suggestion that the programs involve dole-outs. Thus, the Rice Subsidy Program is also called “Rice for Work." It aims to augment the incomes of about two million small-scale farmers and fishers nationwide during lean months following the harvest season. The DSWD says it is equivalent to their wages for 14 days’ work in a month.

Like the beneficiaries for the CCT, the farmers and fisherfolk who will benefit from the Rice for Work program will be selected through the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction (NHTS-PR). Supposedly, the distribution of rice subsidies had already begun last May 15.

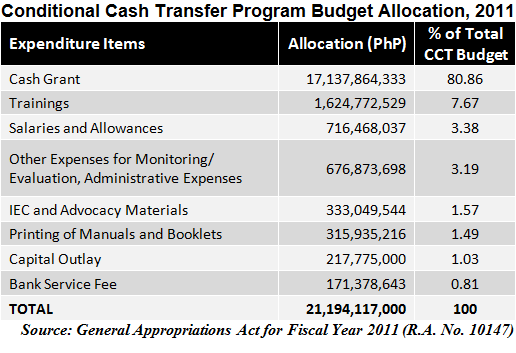

The CCT’s P21 billion, meanwhile, is meant for distribution among 2.3 million poor households by year end. It’s an ambitious undertaking that poses a huge administrative challenge for DSWD to implement. Accordingly, it will also extract a substantial cost, as a closer scrutiny of Republic Act No. 10147 or the GAA for Fiscal Year 2011 reveals.

In other words, not every centavo of that P21 billion will go to poor families. Also eating up a hefty portion of the budget are amounts earmarked for activities related to disbursing those cash grants and for keeping the entire undertaking up and running. The budget for these operational, administrative, and capital outlay altogether amounts to about P4 billion, or a fifth of the total CCT budget.

Translated, that means that for every P100 that the government will be spending for the CCT this year, P80 will go directly to poor families as “cash grants," while the remaining P20 will be spent in the course of bringing that money to them. And that’s not even counting the P100-million budget for selecting the recipients of cash transfers through the NHTS-PR.

A Cabinet secretary said the huge administrative cost of the CCT that is being implemented “top-down" is an attempt by the Aquino government to plug “leakages to corruption," which marred many pro-poor projects in the past that were implemented “bottom-up" or with local government agencies as coordinators.

It’s an overhead cost that seems really huge. But the DSWD sees it as a necessary investment that would help ensure that the program would be free of leakages and shielded from political influence.

That goal, coupled with the magnitude of the undertaking, prompted DSWD to hire thousands of personnel, albeit on a contractual basis. Most of these personnel – called municipal links (MLs) and city links (CLs) – are social workers, but they are not to be confused with municipal social welfare and development officers (MSWDOs) who are employed by the local government unit (LGU). So while the MSWDOs report to the mayor, the MLs and CLs report to DSWD’s regional offices.

The agency has offices in the 16 administrative regions of the country, excluding the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, but does not have units from the provincial level down. All local social welfare and development offices are under the supervision of governors and mayors.

Under the CCT, the DSWD is now scheduled to hire 2,300 contractual ground monitors – the MLs and the CLs – fattening its staff complement twice over.

Among the tasks of the CL/MLs are to coordinate with beneficiaries regarding cash-grant transmittals, as well as with municipal social workers on the conduct of family development sessions. The CL/MLs also monitor compliance of the beneficiaries to the CCT’s conditions and serve as the first line of grievance redress.

To make sure that each ML or CL will be able to closely monitor each CCT family, each is assigned 1,000 beneficiaries. There are about 2,000 CL/MLs under the DSWD’s employ at present, but by the end of the year, that figure is expected to reach 2,300. By then, the department expects to have 2.3 million CCT beneficiary-families.

That also means the DSWD will be spending P34.5 million a month or about P414 million annually just for the salaries of the CL/MLs, each of whom gets P15,000 a month.

But the GAA lists even a bigger amount under “Salaries and Allowances" for the CCT since there are other DSWD personnel (newly hired and otherwise) who are also involved in the program. According to Soliman, such involvement would make the program “integrated within the agency rather than (have) a separate foreign-assisted program unit…that will end when there is no more funding."

But it’s actually “trainings" (sic), not salaries, which are the second largest cost item in the CCT budget. For this year, the “trainings" allocation is P1.6 billion, or monthly expenses for the item of P135 million or P4.45 million per day. The DSWD argues, though, that this would ensure that the CL/MLs and DSWD staff would be able to do all the tasks assigned them for CCT.

There are mechanisms for monitoring DSWD’s performance and accountability for the program. For instance, a GAA special provision specifically requires DSWD to “submit to the DBM, the House Committee on Appropriations and Senate Committee on Finance separate quarterly reports on the disbursements made for the Program or post on its official website, at least on a quarterly basis, the beneficiaries identified under the NHTS-PR National, utilization of amounts, status of implementation, program evaluation and/or assessment reports."

The DSWD has transmitted its first-quarter report on the CCT, according to a staffer of Sen. Franklin M. Drilon, chair of the Senate Committee on Finance. The report was dated April 18, 2011, or two weeks after the close of the first quarter. No copies of the report, however, have been disclosed as of this writing.

With such a big increase in the CCT budget, President Aquino himself found it prudent to have yet another mechanism for monitoring the program. Inserted in the special provisions is the president’s veto: “The Oversight Committees on Public Expenditures herein created in the Senate and House of Representatives shall strictly monitor the effective implementation of the (CCT) Program." – PCIJ, May 2011

Will giving cash to the poor help solve poverty?

CHE DE LOS REYES, PCIJ

05/30/2011 | 10:06 AMFirst of Three Parts

SHE HAD neither bought a lotto ticket nor joined a TV game show. But Marissa felt like she won the jackpot anyway late last year, when her family was chosen as one of the recipients of the government’s Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) Program.

After all, it meant her family would be receiving P800 a month, and while that has since proved inadequate to sustain her brood of four, whatever cash she can lay her hands on is welcome, especially now that her husband, a returnee from suddenly protest-prone Saudi Arabia, has been jobless for the last two months.

Since 2007, some 1.4 million poor households have been selected to receive regular cash grants from the government under the CCT. By the end of this year, the government wants to increase the figure to 2.3 million families.

In the next five years, the government will be enrolling even more families in the CCT; by the time President Benigno Simeon ‘Noynoy’ C. Aquino III’s term ends in 2016, up to 4.6 million poor families would have been covered by the program.

That is the promise of the Aquino government, according to Social Welfare and Development Secretary Corazon ‘Dinky’ Soliman, the CCT’s national program director. But the Philippine Development Plan for 2011 to 2016 – that the government finally released last May 26 – puts the total CCT target-beneficiaries at only 4.3 million by 2016, or 300,000 fewer families.

Also called the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), the CCT is called “the cornerstone of the government’s strategy to fight poverty and attain" the Millennium Development Goals that the Philippines has pledged to achieve by 2015.

Put simply, the CCT – actually a continuation of a program initiated by Aquino’s immediate predecessor, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo – is expected to provide a safety net that will keep impoverished Filipinos from sliding to deeper penury.

Now described as “the world’s favorite new anti-poverty device," CCTs have been differently funded and implemented in virtually all the countries of Latin America and some in Asia and other continents since 1995.

Development scholars and analysts have largely affirmed the good if short-term outcomes that CCTs could trigger such as better school-enrollment ratios and improved health status of the children of CCT beneficiary families.

At the same time, however, they have also expressed concern over the long-term impact and benefits of costly CCT programs, especially if these are not complemented by real, massive spending to ramp up the quantity and quality of education and health services, as well as job-generation and livelihood-training programs for the poor, adult population. Moreover, they warn that sustainability could become a serious problem once the funds run out and there is no all-sided strategy against poverty in place.

In fact, such concerns have made other countries proceed with caution with their CCTs. In Latin America where CCTs first took root, governments first rolled out the program on the local level, or in some pilot areas, before going full blast with a national rollout.

But this is apparently not the case in the Philippines, where a premature expansion of the scope of the CCT, as well as the rush in the implementation of the program, may jeopardize what many still consider as a promising “flagship program" in the Aquino administration’s double-barreled drive against poverty and corruption.

Worrisome findings

A posse of Pantawids

THE straight and narrow path, or “matuwid na daan" in Filipino, is where President Benigno Simeon ‘Noynoy’ C. Aquino III says he wishes all Filipinos would tread. And perhaps to prove that he’s not all talk and no action, Aquino has splurged billions of pesos on many “pantawid" (“tide over" in English) programs that all involve cash subsidies for the poor.

The biggest of these “pantawid" initiatives, of course, is the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) or the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) that has been allotted P21 billion in the 2011 General Appropriations Act (GAA), and a substantial part of it funded with loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Three other programs are also listed under the 4Ps, each with its own hefty budget: the “Supplemental Feeding Program" (P2.88 billion), “Food for Work for Internally Displaced Persons" (P881 million), and “Rice Subsidy Program" (P4.23 billion). Altogether, these other subsidy programs are worth an additional P8 billion.

Read more

Six months of the PCIJ’s research and review of relevant documents, and interviews with relevant sources on the CCT reveal it to be a focused, time-bound initiative only for poor Filipino families who would pass the computer-generated targeting of beneficiaries under a “proxy means test," and then would have to comply with strict program conditionalities. Under these terms, the poorest of the poor, notably the “food poor" and the most destitute that walk the streets and do not belong to typical “family" units, are not the targets of the CCT.

The decision to expand and accelerate the program was also made without adequate due diligence in assessing supply-side, implementation, and program delivery requirements. The program’s target beneficiaries have been increased seven-fold from 2008 to this year even without a full assessment of the availability, quantity, and quality of education and health services in all CCT areas, or even before a comprehensive evaluation of the program’s first phase under the Arroyo administration could be made.

The CCT has been paraded in multiple road-show activities even before the formal launch of the Philippine Development Plan or PDP for 2011 to 2016 that should serve as the administration’s governance and growth framework. The odd sequence of events has yielded a disparity in the number of CCT target-beneficiaries. Soliman, the President and other senior officials have boasted that the CCT would benefit 4.6 million households by 2016; the PDP says it would only be 4.3 million.

Soliman’s number is pegged on the 2006 Official Poverty Statistics. The National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) has finished the 2009 Official Poverty Statistics, which counts a different number of poor households, but the DSWD’s targeting of CCT households is stuck on the 2006 version.

Across the Philippines, the NSCB said there were 3,670,791 poor families by 2006, and 3,855,730 by 2009.

For sure, the program’s expansion and accelerated implementation will not come cheap. It involves mainly the giving of cash of up to a maximum of P1,400 each to 4.6 million families. A significant portion of those funds (whose total runs up to tens of billions of pesos) are coming from loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in the next five years, raising the question of whether or not the government can sustain the program beyond 2016.

Billions of pesos have also been allotted for personnel and administrative systems to monitor the beneficiaries’ compliance (demand side) with CCT conditions, even as there remains no vigorous parallel monitoring of how national and local government agencies will comply with their obligations to deliver on education and health services (supply side) that the CCT promises.

Meantime, the designated lead agency for the CCT, the Department of Social Welfare ad Development (DSWD), is now under intense pressure to accomplish its tasks related to the program, along with its regular duties. To cope with the rushed and expanded implementation of the program, DSWD is hiring, training, and deploying some 2,300 ground monitors (called ‘municipal links’ and ‘city links’ in project documents) at frenetic speed. As budgeted in its 2011 agency appropriation, the DSWD could actually spend up to P4 million on CCT-related “training" activities alone, every day.

This is even as the targeting and enrollment of additional beneficiaries are proceeding just as quickly. On its website, the DSWD has posted a two-slide power-point report saying that as of last March 11, it had already disbursed P744.7 million of cash grants. It said it expects to ramp up its cash grants disbursement to P2.68 billion by March 31, 2011, or by a phenomenal P1.9 billion in just 20 days.

The DSWD has yet to complete its Supply-Side Assessment (SSA) in 320 of the 729 cities and municipalities that have been listed as “CCT areas" by November 2010, but already the results are way too tragic. Of the 409 CCT towns and cities audited, an overwhelming majority are not meeting seven of the nine quantity benchmarks for education, and all three benchmarks for health personnel ratios to population.

On the ground, though, the picture has become quite complicated. Under the General Appropriations Act of 2011, the CCT funds must be directly deposited to government depository banks, and directly accessed by the beneficiaries. “No DSWD employee/officer, CCT secretariat and local government official shall directly handle funds intended for cash grant," the law says. But because the Land Bank of the Philippines, the CCT fund depository bank, has no branches in many CCT areas, the DSWD has lately enrolled pawnshops and mobile cash-transfer outlets to serve as distribution centers of the cash grants.

Unsurprisingly, even beneficiaries are now raising queries about the program, with some expressing doubt that they would be able to comply with the conditions that come with the CCT grants. Others are pointing to unexplained bulk disbursements that have been followed by delayed payouts as signs that the system is still far from being efficient.

Thousands of poor families are also wondering why they were left out and if there is a chance for them to be included in the program in the future.

Surprised client

Marissa herself was surprised when her family was among more than 900 selected for the CCT in her community in Metro Manila. When the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) conducted its survey to help it pick CCT beneficiaries last year, Marissa’s husband was still working as a cook abroad and earning the equivalent of P15,000 a month.

In Marissa’s community – a former dumpsite that is now populated by street hawkers, manual laborers, and factory workers, along with hordes of the unemployed – that was, and is still, considered a princely sum. (All of the people PCIJ interviewed in that community, Marissa included, asked that their real names not be used for this story.)

By the government’s own definition, Marissa’s family was not poor at the time of the survey. To be considered poor, a family with six members residing in Metro Manila should be earning a monthly income below P9,901 in 2009. This is the so-called ‘poverty threshold,’ which the NSCB defines as “the minimum income required for a family to meet the basic food and non-food requirements."

State researchers say that minimum income will enable a family to feed all its six members three nutritionally adequate meals and one snack (for a total of 2,000 calories a day, on average) and pay for basic necessities such as clothes and footwear; housing; fuel, light and water; medical care; education; and transportation and communication, among others.

Income-poor families, says the NSCB, now number 3.86 million – or about two in every10 families. There are also about 1.45 million families who are “food poor," or those not earning enough to eat three nutritionally adequate meals a day. According to the NSCB, a family of five in Metro Manila would need at least P5,763 monthly to be able to have such daily meals.

By dint of hard work, Lorie, a widowed mother of four, has made it possible for her family’s income to make it to that NSCB benchmark. Yet her family obviously still falls under the income-poor category, and can be considered ‘chronic poor’ – which is why Lorie can’t understand why she was overlooked by the CCT.

In what sounds like a reference to “unlikely" beneficiaries like Marissa’s family, Lorie, a resident of the same shanty community that Marissa calls home, wonders aloud: “It’s puzzling. There are those whose husbands are working abroad, whose houses are made of concrete – why were they included in the 4Ps and I wasn’t?"

Lorie depends on her dead husband’s social security pension of P4,200 a month, which she tries to augment in whatever way she can. For instance, she operates a sari-sari store that earns her about P100 a day. She also washes pots for a neighbor’s food stall, for which she gets P70 a day. But even then, she often finds herself short of cash, and she would be unable to keep her store running if she were to lose her line of credit from small-time lenders in the community.

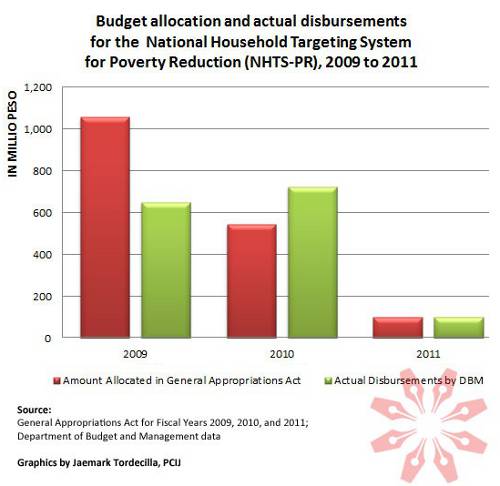

Lorie says she was told the selection had been done “by a computer." But the process is actually far more complicated than that. Dubbed as the “National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction (NHTS-PR)" and launched in 2009, the system for selecting CCT beneficiaries was designed supposedly to prevent cash benefits from leaking to the non-poor.

‘Proxy means test’

First, DSWD hired 21,892 workers, including enumerators who would conduct house-to-house interviews across the country. But instead of asking households directly about their income and expenditure, DSWD used a ‘proxy means test’ wherein 34 questions were asked to gather information about a household’s socioeconomic condition, such as the family members’ education, their tenure status, house construction material, appliances and furniture, and whether a member is working abroad, among others.

DSWD prioritized the 20 poorest provinces and municipalities. In other areas, the agency focused on “pockets of poverty" or areas where clusters of poor households reside, such as in Marissa and Lorie’s community.

A computer model calculated the approximate income per capita of the household and ranked them in reference to the poverty threshold of the province or the district in the National Capital Region (NCR). To qualify for the CCT, a family’s economic condition must be equal to or below that threshold.

Yet DSWD’s Soliman herself admits that the system isn’t foolproof. That’s why, she says, the DSWD has been correcting the errors made by enumerators – whether done inadvertently or on purpose – through a grievance system whereby people could contact DSWD through text or email. But for the likes of Lorie, an easier option would be ‘on-demand application’ whereby one could go to designated areas in the municipality and have oneself included in DSWD’s database.

In both options, DSWD will validate the family’s eligibility. As of last March 10, a total of 43,000 families have been delisted from the program while 80,000 have been added, according to Soliman.

That, however, brings little consolation for Lorie, who already joined the on-demand application twice but still failed to make it to the list.

Being part of a poor municipality and on or below the provincial poverty threshold are not the only criteria to qualify for consideration for the CCT, though. The poor household must also have one or more children below 15 years and/or a pregnant woman at the time of the DSWD’s assessment.

Strings attached

Once selected, a CCT household would get P500 a month at least. There is also a P300-monthly education grant for every child aged three to 14 in that household; this would be given 10 months in the year for up to three children per family. Each CCT family can be part of the program for a maximum of five years.

For the poorest families, sending a child to school often means foregoing a meal or two for the rest of the family members, says Soliman.

With the CCT cash, these families in theory would now be able to send their children to school and leave their budget for food intact.

But it’s money with strings attached. Beneficiaries need to comply with conditions that include pre- and post-natal care for those who are pregnant, preventive health check-ups for children zero to five years old, and 85-percent school attendance by children three to 14 years old.

In addition, parents must attend family development sessions every month in an area designated in coordination with the local government. These include responsible parenthood sessions, mothers’ classes, and parent-effectiveness seminars.

Compliance check

The DSWD says these conditions are necessary to “encourage parents to invest in their children’s (and their own) human capital through investments in their health and nutrition, education, and participation in community activities." The program’s proponents also say this is what essentially differentiates CCT from a dole out.

DSWD monitors compliance by having school and municipal health personnel record school attendance and health check-ups. Compliance reports are timed with the cash releases that take place every two months. A family that fails thrice to comply with the conditions is suspended from the program. After the fourth offense, the errant family can be dropped completely from the program.

“It’s also possible," says 4Ps public relations officer Pamela Caperiña-Susara, “that the child or whoever did not comply would be the only one dropped from the program, not the entire family."

But such conditions seem to have been thrown out the window in Marissa’s community last November, the same month they were enrolled as CCT beneficiaries. They were expecting to be given two months (November-December) worth of grants as their first payout, but instead they received money for the 12 months of 2010, including for the 10 months when they were not yet CCT beneficiaries. Each of the families received a lump sum, which sent many of them on a tailspin.

For instance, however hard Marissa and her neighbors tried to crunch the numbers, they couldn’t figure out exactly how much each of them was supposed to receive.

According to DSWD, a family who has three qualified children should receive P15,000 in a year.

In Marissa’s community, however, some families with three children reportedly received less than that amount, while others received P15,000 despite having less than three children.

Since it was nearly Christmas, most of the parents who received lump sums used the money to buy clothes and shoes for their children. Some mothers also used the money to buy milk and vitamins. Marissa observes, however, that this was probably because they thought they were going to be monitored right away.

Not so responsible

In fact, other parents were less than responsible with that first cash grant. Some of them were even caught gambling by the city link – the DSWD personnel assigned to assist beneficiaries – who then confiscated their ATM cards, which gave them access to their special CCT accounts at the Land Bank.

Sought for explanation by PCIJ, DSWD even admits that the lump-sum disbursements were not isolated to Marissa’s community. It says its personnel had to temporarily stop certain CCT-related activities across the country while the May 10, 2010 elections ban was in force. This particularly affected the registration and validation of beneficiaries and the transmittal of cash grants during that period.

DSWD was able to resume CCT activities only in the third quarter of 2010. To compensate for the delay, the department disbursed several months worth of cash grants; in some cases, these reached a year’s worth.

Meanwhile, DSWD says inaccuracies in the information given and/or entered in the assessment forms during the selection survey could explain the discrepancies in the amounts that the beneficiaries received. These could include incorrect numbers and ages of children that the household declared, it says.

The irony is that since receiving that sudden bonanza, Marissa and the other CCT beneficiaries in her community have not gotten a centavo of their bi-monthly grants for this year, and no one knows why. As far as they know, they repeat, every CCT family there received lump sums for 2010 and nothing else since. Not surprisingly, the situation has not only led them to scratch their heads, but also to cast a wary eye on the program.

Erratic release

Perhaps because the payout release now appears erratic to her, Marissa says the CCT may not really help keep poor children in school. At the very least, the experience has reminded her that CCT beneficiaries like her shouldn’t rely on the program too much.

“Like they say, it’s just for tiding you over," she remarks. “But…you have to wait another two months."

Then again, the grant amount her family was supposed to receive already had Marissa worried that her family would not be able to comply with the condition regarding education.

Only the youngest of her four children is under the age of 14. Marissa says the monthly P300 from the CCT that is supposed to help that child keep on attending class may not be enough. It translates to a subsidy of P15 a day for the child, who may have a maximum number of only three absences a month to keep on being a CCT beneficiary.

By Marissa’s computation, each child needs at least P20 a day for baon, exclusive of any transportation expense. And even that amount is hardly enough for a nutritious meal. Of course there’s still the P500 that each CCT family gets per month as a health subsidy, but Marissa says her household’s daily food expenses run to P300.

They’re already on a strict budget, since neither she nor her husband is employed at the moment. They’re surviving because after her husband lost his job overseas, Marissa pawned the rights to their house. Part of the proceeds was allocated for her husband’s job-hunting expenses; the rest has been paying the family’s daily expenses. Once that runs out, all that would be left for them to rely on would be the CCT money.

“For poor people like us, it’s really difficult," says Marissa. “For instance, if a child doesn’t have pocket money, he’ll really miss class."

“They’re saying, ‘Why will the child miss school when you’re already receiving cash?’" she adds. “But is the amount really sufficient?"

Big transpo cost

In rural communities especially, poor families often reside in the remotest barangays. Isabelita Escobilla, who hails from a mountain barangay in the Bondoc Peninsula, says that one-way motorcycle fare from their place to the town proper, where the public school is located, costs between P30 to P50.

Health centers are usually in the town proper as well, and these are supposed to be visited by CCT beneficiaries at least once a month. That means they will have to earmark part of their P500 monthly health subsidy for transportation.

Myrna, yet another CCT beneficiary from Marissa’s community, also says that P500 cannot cover the medical expenses of her youngest son, who has chronic asthma and now has primary complex.

On the upside, she says that she can use it to buy the vitamins that her son needs. But what she is really thankful for is the membership in Philhealth’s indigent program that came with her family’s being selected for the CCT. Because of Philhealth, Myrna says that she no longer has to resort to raiding her family’s meager funds whenever her son needs medical care.

Still, all nine CCT beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries that the PCIJ interviewed say the government could help them more effectively if it would provide them with a means of livelihood or a job.

Such a program would also be more sustainable in the long run, they say. Too, people would use their money more judiciously. “Kasi pinaghirapan, eh (Because we had to work hard for it)," says Michelle, an 18-year-old mother of two who was not selected for the CCT.

According to DSWD Secretary Soliman, her agency is linking the CCT with programs that provide micro-credit and guaranteed employment to beneficiaries. Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Cayetano W. Paderanga Jr. himself says that “to be able to reduce poverty, you must generate employment." – PCIJ, May 2011

Monday, May 30, 2011

Making her mark in int’l charity work

Cebuana social worker Mingming Evora is a regional leader of Plan International, a global charity for children and poor communities

By Monica Feria

Philippine Daily Inquirer

2:15 am | Sunday, May 29th, 2011

On her first assignment abroad, Myrna Remata Evora was greeted by death threats and obscene phone calls. A social worker for an international charity organization, Myrna had been sent to Indonesia in 1991 to rationalize the organization’s programs and trim the staff.She even got a call saying she should go home immediately because her husband, an engineer working in Saudi Arabia at that time, had died. It was not true, of course. Another caller (a foreigner like herself) told her, “You do not know who I am, and you are only a woman,” she recalled.

But disgruntled staff members may have underestimated the firmness and determination behind the pleasant smile and gentle manners of this Cebuana native, called Mingming by friends.

Mingming, a product of the University of Southern Philippines who honed her social organizing skills in the slums and leper communities of Cebu, waited it out.

The threatening phone calls eased up after three months. In six months she had a leaner staff and new programs in place. Mingming, who also holds a Master’s degree in social work from the University of the Philippines in Diliman, ended up staying three years in Yogyakarta as a field director for the US and London-based Plan International (Plan), one of the largest charities serving children and depressed communities in the world.

“That was my first and most difficult challenge,” says Mingming, who went on to posts in Bolivia and Sri Lanka before moving to Bangkok to take up the job of regional director of Plan, supervising multi-million dollar charity projects in 14 countries. At the time of this interview she was preparing to take up a new post in Bangladesh where the organization planned to set up one of its global virtual schools to train social workers and staff in a unique Child-centered Community Development (CCCD) approach.

International social work involves big money. Donors from all over the world trust charities to see to it that their money really goes to helping the poor and not to overstaffed bureaucracies and graft. One has to learn to deal with political requirements (sometimes pressure) from local governors regarding certain projects, notes Mingming.

Filipino strengths

Mingming says many of her aces, she learned while growing up in a poor family in the Philippines. For one, “pakisama (the Filipino trait of social adaptability),” she says. In Indonesia she wore her hair long like the other women, learned Bahasa, ate what they ate, and acquainted herself with their social rules. In Sri Lanka she came to work in a sari.

But pakisama, here or elsewhere, says Mingming, only works when people see that you are genuinely sincere in showing your solidarity. In Bolivia, she loved their milk and cheese, but candidly admitted to her Bolivian friends that she didn’t really like the taste of lamb.

Pakisama is not “pakitang tao” (just for show). If you are just acting, sooner or later lalabas din yan (it will come out),” she says. And of course, it has its limits, too.

She also learned early on that being poor did not necessarily rule out being respected in a community. “My parents were teachers. We were poor. We did not own our own house,” she recalls. She and her siblings had to help care for the pigs in the backyard to earn their school tuition money.

LEARNING WITHOUT FEAR Thai Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva had presented Plan Asia Regional Office Director Myrna Evora with a pledge of support for Plan International’s “Learn without Fear” campaign, an advocacy to end violence in schools. At left, Evora joins Nepalese women of the Urbalari Child Club.

Mingming remembers this when she meets people who seem to discriminate against representatives or employees from poor countries. Like many Southeast Asians, Mingming is prone to be non-confrontational. But she says her parents had given her an inner confidence that allows her to stick to her guns.

Making every cent count

Mingming was in charge of Plan projects in Sri Lanka when a tsunami struck, killing over 30,000 villagers. Plan helped build over 250 new houses.

There were many donors from all over the world who wanted to help, she recalls. A lot of money was pouring in. At one point, Mingming noticed that there were more pledges for houses than there were families affected. Some houses were also being planned in places where there was no water and electricity, and were too far from the residents’ places of work. Construction was going on at such a fast pace, that some of the bricks used to build houses melted at the first rain.

Mingming put a stop to it. She even turned away some donors. “It’s my job to tell them the truth, even if it means accepting some initial shortcomings of our own, or antagonizing the local government or construction industry,” she says.

Being in charge of other people’s donations can be stressful work. But Mingming says the satisfactions of social work still outweigh the anxieties.

A humbling experience

Despite cultural differences, the look of poverty is the same everywhere, she says. “You see it in the eyes of poor children in any country.” It’s an expression that has never failed to touch her heart and those of many people throughout the world.

“How can I complain about the weather or the food or my work problems when these people are worse off than me?” she muses, adding that social work is “a very humbling experience.”

“It can also be frustrating. Some people think some poor people don’t seem to want to help themselves.” Well, she says, this is why social work needs to be professionalized. There are ways of helping poor people help themselves, she says, adding that people need to be given help with their dignity intact.

Plan International, she says, endorses a rights-based approach to development and is focusing on children. It also keeps an eye on gender and environment issues when approving projects.

She has grown as a professional during her experience abroad. She says she hopes the Philippines will be her last post, so she can better share everything she has learned with communities back home.

Her advice to other Filipino social workers who may find themselves in similar jobs abroad: Be yourself, be sincere; it’s your best asset. But also, upgrade your professional skills, be consistent and deliver…”

Pursuing a global career has kept Mingming away from her family for long stretches of time. She gives thanks to strong extended family support for helping her weather the stresses of long-distance mothering. She also thanks her children, who have accepted her as an overseas career mom.

Global career mom

THE CHILDREN’S CHALLENGE Evora says ‘game’ to the hula hoop challenge hurled by tribal children in the mountain villages of Laos

“Communication is important,” she advises other overseas moms. Her children also visited her in her place of work twice or thrice a year.

For mothers, there are pros and cons of working overseas. But “it can be done,” she says.

Mingming shares (with the permission of her daughter) a heartwarming note: “Dear mom … I hope that when I become a mom myself, I’ll be like you—able to teach my kids the value of the peso but being generous and kind-hearted as well. I hope my kids will grow up responsible din (also) and ambitious…Thanks for everything mom! love you!”

Sunday, May 29, 2011

Seven ‘Thou shall nots’

Viewpoint

By: Juan L. Mercado

Philippine Daily Inquirer

9:55 pm | Friday, May 27th, 2011

THE 20 percent Local Development Fund (LDF) is the “most abused” budget item today, Local Government Secretary Jesse Robredo told local officials at a Cebu conference. LDFs are spent by 79 provinces. (The Supreme Court, however, reversed itself on Dinagat Island’s status. So, make that 80.) This trust fund is also vital for 122 cities, including the 16 towns on whose cityhood ambition the Court flipped, and then flopped. A reconsideration motion is pending. Add to that roster 1,512 towns.

Six out of every 10 local governments flunk the “full disclosure” criterion on tax spending. This fractures the General Appropriations Act of 2011 and the Local Government Code. Both require “full disclosure to ensure transparency and accountability,” Robredo says.

This Magsaysay awardee’s candor causes some to fume. “Does the DILG control all LGUs?” snapped Dumanjug Mayor Nelson Garcia. He is the national vice president of the League of Municipalities. The league will challenge DILG memo circular 2010-138 before the Supreme Court.

Robredo’s Dec. 7 memo lists seven “Thou shall nots” in disbursing LDF. Bohol Gov. Edgar Chatto, thus, flags a mayors’ manifesto that bucks curbs on their spending.

What is the LDF? How did this trust fund come about? And what is its track record?

“Thou shall not ration justice,” Justice Learned Hand once cautioned. Does Memo 2010-138 deny local officials equity?

Recall the 1972 UN Environment Conference in Stockholm. Delegates from 113 countries, including the Philippines, adopted an action plan that proposed a “20-20 Pact.” Governments agreed to earmark 20 percent of resources for the poorest. Such fund would address the needs of the most deprived: nutrition, health care, medicine, potable water, sanitation, primary schooling, etc.

Human development relieves grinding poverty, the Stockholm consensus stressed. Curbing disease and death rates makes human development possible. Unmet human needs usher more pre-school children in the Philippines to premature graves than in Egypt, Kenya or Tanzania, the Asian Development Bank noted.

Former Sen. Aquilino Pimental wove that 20 percent vital safety net concept into the Local Government Code. Viewpoint noted (Inquirer, 10/23/07) that politicians converted the LDF into their mini-pork barrels, as successive COA audits found.

Davao Oriental Sanggunian officials ladled P669,892 as “financial assistance”—for themselves. Dapitan doled P1 million for an “executive band.” San Carlos City allocated P110,000 for a Boy Scouts jamboree in Angeles. Northern Samar purchased seven brand-new vehicles. Cebu City Mayor Tomas Osmeña’s barangay leaders bought themselves high-powered motorcycles and handguns.

Plunder of the LDF does not stem from ignorance. Ruling after ruling underscore its “preferential option for the poorest.”

Could the LDF supplement salaries of national high school teachers? Mountain Province and Ifugao officials asked. Could it patch funding deficits in other projects?

No way, Jose, said DILG Opinion No. 5 dated Aug. 10, 1999.

That policy remains in force today. But it is honored more in the breach than in practice.

Match some of Robredo’s “Thou shalt nots” with specific cases.

Underwriting “salaries, wages or overtime pay” is verboten, the memo says. In contrast, the COA annual report on local governments has an unvarying gripe: “Regular expenses, such as salaries, wages, facilities maintenance, travel, celebration of festivities, etc. are charged to LDF.”

In 2008, for example, 102 LGUs failed to implement development projects, the COA reported. The same sordid pattern persisted into the next year. It continues today.

Thou shall not underwrite “administrative expenses such as cash gifts, bonuses, food allowances, medical assistance, uniforms, supplies, meetings, communication, water and light, petroleum products, and the like,” Robredo’s memo tells LGUs.

Fifth-class town Aloguinsan in Cebu splurged P540,000 for a live concert and a dance-breakout, the COA said. Borbon town granted P24,000 to each department head. Jagna, Bohol, fittered away P1.85 million in LDF resources for heavy equipment.

Cotabato City appropriated P55 million of its LDF for three development projects. It spent P44.3 million mostly on creating jobs, not meeting basic human needs.

“Evaluation conducted by the Audit Team Leader disclosed that majority of programs, implemented by the city government under the 20 percent (Fund) consist of augmentation of manpower requirements,” the COA said. Some 480 workers were assigned/detailed at the 27 offices of the city. That chewed up P16.3 million.

Junkets or akbay aral are out, Robredo says. “Traveling expenses, whether domestic of foreign” may not be billed to the LDF.

Neither may officials dip into the fund for “registration fees in training, seminars, conferences or conventions.”

Minglanilla officials (Cebu) burned P5.6 million from the LDF for two trips to join Palawan’s Kabunhawan festival. Lapu-Lapu City’s Association of Barangay Councils “misused” P550,000 on a Christmas party and gifts over two years and P776,500 on honoraria for 30 barangay captains.

A new Performance Challenge Fund will provide P500 million to 344 LGUs that provide counterparts from LDFs for essential projects. These range from rural health units and water and sanitation to post-harvest facilities.

Local officials stubbornly insist on having their LDF pork barrels.

“These are all honest men,” the old adage says. “But why can I not find my bag?”

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Editorial: Charity, please

A PASTORAL letter from Archbishop Socrates Villegas of Lingayen-Dagupan strikes a note not often heard in the controversy over the reproductive health bill pending in Congress: moderation. “We want to make a plea for greater charity even as we passionately state our positions on this divisive issue. At the end of the heated debates, we will all be winners if we proclaim the truths we believe in with utmost charity, courtesy and respect for one another.”

The pastoral statement will only be read in all churches in the archdiocese of Lingayen-Dagupan this Sunday, but already it is making the rounds, passed from hand to hand or e-mail account to e-mail account. It is not hard to see why; the letter is a welcome call for the “triumph of reason and sobriety.” In the same spirit of charity and candor, however, we must point out an unsettling truth: the archbishop’s statement is better directed at some of his fellow bishops and priests who have led the fire-and-brimstone opposition to the RH bill.

Even before the present Congress convened, some leaders of the Roman Catholic Church in the heat of the election campaign last year already issued threats to excommunicate those political candidates who supported a reproductive health agenda. That hostile stance, lacking in the very “charity, courtesy and respect” Archbishop Villegas now speaks of, set the tone for much of the Church’s engagement with the RH bill issue. Since then, the extremist position was reinforced by threat after high-profile threat: of communion being possibly withheld, of churchgoers known for their pro-RH bill position being told they were unwelcome in church, of RH bill advocates being harassed by chants of “Your mother should have aborted you.” While the true Church teaching on the vexing issue of contraception is well-reasoned and even nuanced (as Pope Benedict XVI’s remarks in “Light of the World” proved), the extremist position adopted by a number of bishops and priests and laymen became absurdly reductionist, equating the concept of reproductive health itself with either abortion or licentiousness.

(There is also the not insignificant matter of Villegas’ predecessor, Archbishop Oscar Cruz, adopting a stance against President Aquino that could only be categorized as personal, including his uncharitable notion, certainly not something that will find support in the Church’s teachings, that a man like the President who is past 50 is effectively disqualified from a happy marriage.)

The lack of charity, courtesy and respect touched bottom when a bishop decided it was time to pull out of the high-level dialogue with Malacañang, because Malacañang, he said, was no longer open to discussion. In fact it is the bishops who can be accused of inflexibility in position.

Thus, when Villegas writes the following—“The past few months have seen many of us who belong to the same Church and who share the same faith in Christ at odds with one another on the issue of the reproductive health bill in Congress. It is indeed sad and perhaps even scandalous for non-Christians to see the Catholic flock divided among themselves and some members of the Catholic lay faithful at odds with their own pastors. If we fail to have love, we make ourselves orphans.”—charity and candor impel us to point out that sometimes the orphaning is done by the pastors themselves.

We do not wish to suggest that the Villegas pastoral letter can be interpreted as being pro-RH bill. The good bishop’s appeal to a return to conscience is based squarely on the serene conviction that the right thing to do is to oppose the bill. “We pray conscience does not allow itself to be swayed by statistics or partisan political positions. The only voice conscience must listen to is the voice of God.” Elsewhere he also writes: “The issue of contraception belongs to the realm of faith not opinions.”

But he exemplifies his own appeal for reasoned debate, and it is a call we should heed. “We appeal to our Catholic brethren who stand on opposing sides on the reproductive health bill to return to the voice of conscience, to state their positions and rebut their opponents always with charity.” Now that is something all Filipino Catholics can agree on.

The pastoral statement will only be read in all churches in the archdiocese of Lingayen-Dagupan this Sunday, but already it is making the rounds, passed from hand to hand or e-mail account to e-mail account. It is not hard to see why; the letter is a welcome call for the “triumph of reason and sobriety.” In the same spirit of charity and candor, however, we must point out an unsettling truth: the archbishop’s statement is better directed at some of his fellow bishops and priests who have led the fire-and-brimstone opposition to the RH bill.

Even before the present Congress convened, some leaders of the Roman Catholic Church in the heat of the election campaign last year already issued threats to excommunicate those political candidates who supported a reproductive health agenda. That hostile stance, lacking in the very “charity, courtesy and respect” Archbishop Villegas now speaks of, set the tone for much of the Church’s engagement with the RH bill issue. Since then, the extremist position was reinforced by threat after high-profile threat: of communion being possibly withheld, of churchgoers known for their pro-RH bill position being told they were unwelcome in church, of RH bill advocates being harassed by chants of “Your mother should have aborted you.” While the true Church teaching on the vexing issue of contraception is well-reasoned and even nuanced (as Pope Benedict XVI’s remarks in “Light of the World” proved), the extremist position adopted by a number of bishops and priests and laymen became absurdly reductionist, equating the concept of reproductive health itself with either abortion or licentiousness.

(There is also the not insignificant matter of Villegas’ predecessor, Archbishop Oscar Cruz, adopting a stance against President Aquino that could only be categorized as personal, including his uncharitable notion, certainly not something that will find support in the Church’s teachings, that a man like the President who is past 50 is effectively disqualified from a happy marriage.)

The lack of charity, courtesy and respect touched bottom when a bishop decided it was time to pull out of the high-level dialogue with Malacañang, because Malacañang, he said, was no longer open to discussion. In fact it is the bishops who can be accused of inflexibility in position.

Thus, when Villegas writes the following—“The past few months have seen many of us who belong to the same Church and who share the same faith in Christ at odds with one another on the issue of the reproductive health bill in Congress. It is indeed sad and perhaps even scandalous for non-Christians to see the Catholic flock divided among themselves and some members of the Catholic lay faithful at odds with their own pastors. If we fail to have love, we make ourselves orphans.”—charity and candor impel us to point out that sometimes the orphaning is done by the pastors themselves.

We do not wish to suggest that the Villegas pastoral letter can be interpreted as being pro-RH bill. The good bishop’s appeal to a return to conscience is based squarely on the serene conviction that the right thing to do is to oppose the bill. “We pray conscience does not allow itself to be swayed by statistics or partisan political positions. The only voice conscience must listen to is the voice of God.” Elsewhere he also writes: “The issue of contraception belongs to the realm of faith not opinions.”

But he exemplifies his own appeal for reasoned debate, and it is a call we should heed. “We appeal to our Catholic brethren who stand on opposing sides on the reproductive health bill to return to the voice of conscience, to state their positions and rebut their opponents always with charity.” Now that is something all Filipino Catholics can agree on.

Monday, May 23, 2011

My stand on the RH Bill

Sounding Board

By: Fr. Joaquin G. Bernas S. J.

Philippine Daily Inquirer

1:49 am | Monday, May 23rd, 2011

I HAVE been following the debates on the RH Bill not just in the recent House sessions but practically since its start. In the process, because of what I have said and written (where I have not joined the attack dogs against the RH Bill), I have been called a Judas by a high-ranking cleric, I am considered a heretic in a wealthy barangay where some members have urged that I should leave the Church (which is insane), and one of those who regularly hears my Mass in the Ateneo Chapel in Rockwell came to me disturbed by my position. I feel therefore that I owe some explanation to those who listen to me or read my writings.

First, let me start by saying that I adhere to the teaching of the Church on artificial contraception even if I am aware that the teaching on the subject is not considered infallible doctrine by those who know more theology than I do. Moreover, I am still considered a Catholic and Jesuit in good standing by my superiors, critics notwithstanding!

Second (very important for me as a student of the Constitution and of church-state relations), I am very much aware of the fact that we live in a pluralist society where various religious groups have differing beliefs about the morality of artificial contraception. But freedom of religion means more than just the freedom to believe. It also means the freedom to act or not to act according to what one believes. Hence, the state should not prevent people from practicing responsible parenthood according to their religious belief nor may churchmen compel President Aquino, by whatever means, to prevent people from acting according to their religious belief. As the “Compendium on the Social Teaching of the Catholic Church” says, “Because of its historical and cultural ties to a nation, a religious community might be given special recognition on the part of the State. Such recognition must in no way create discrimination within the civil or social order for other religious groups” and “Those responsible for government are required to interpret the common good of their country not only according to the guidelines of the majority but also according to the effective good of all the members of the community, including the minority.”

Third, I am dismayed by preachers telling parishioners that support for the RH Bill ipso facto is a serious sin or merits excommunication! I find this to be irresponsible.

Fourth, I have never held that the RH Bill is perfect. But if we have to have an RH law, I intend to contribute to its improvement as much as I can. Because of this, I and a number of my colleagues have offered ways of improving it and specifying areas that can be the subject of intelligent discussion. (Yes, there are intelligent people in our country.) For that purpose we jointly prepared and I published in my column what we called “talking points” on the bill.

Fifth, specifically I advocate removal of the provision on mandatory sexual education in public schools without the consent of parents. (I assume that those who send their children to Catholic schools accept the program of Catholic schools on the subject.) My reason for requiring the consent of parents is, among others, the constitutional provision which recognizes the sanctity of the human family and “the natural and primary right of parents in the rearing of the youth for civic efficiency and the development of moral character.” (Article II, Section 12)

Sixth, I am pleased that the bill reiterates the prohibition of abortion as an assault against the right to life. Abortifacient pills and devices, if there are any in the market, should be banned by the Food and Drug Administration. But whether or not there are such is a question of scientific fact of which I am no judge.

Seventh, I hold that there already is abortion any time a fertilized ovum is expelled. The Constitution commands that the life of the unborn be protected “from conception.” For me this means that sacred life begins at fertilization and not at implantation.

Eighth, it has already been pointed out that the obligation of employers with regard to the sexual and reproductive health of employees is already dealt with in the Labor Code. If the provision needs improvement or nuancing, let it be done through an examination of the Labor Code provision.

Ninth, there are many valuable points in the bill’s Declaration of Policy and Guiding Principles which can serve the welfare of the nation and especially of poor women who cannot afford the cost of medical service. There are specific provisions which give substance to these good points. They should be saved.

Tenth, I hold that public money may be spent for the promotion of reproductive health in ways that do not violate the Constitution. Public money is neither Catholic, nor Protestant, nor Muslim or what have you and may be appropriated by Congress for the public good without violating the Constitution.

Eleventh, I leave the debate on population control to sociologists.

Finally, I am happy that the CBCP has disowned the self-destructive views of some clerics.

By: Fr. Joaquin G. Bernas S. J.

Philippine Daily Inquirer

1:49 am | Monday, May 23rd, 2011

I HAVE been following the debates on the RH Bill not just in the recent House sessions but practically since its start. In the process, because of what I have said and written (where I have not joined the attack dogs against the RH Bill), I have been called a Judas by a high-ranking cleric, I am considered a heretic in a wealthy barangay where some members have urged that I should leave the Church (which is insane), and one of those who regularly hears my Mass in the Ateneo Chapel in Rockwell came to me disturbed by my position. I feel therefore that I owe some explanation to those who listen to me or read my writings.

First, let me start by saying that I adhere to the teaching of the Church on artificial contraception even if I am aware that the teaching on the subject is not considered infallible doctrine by those who know more theology than I do. Moreover, I am still considered a Catholic and Jesuit in good standing by my superiors, critics notwithstanding!

Second (very important for me as a student of the Constitution and of church-state relations), I am very much aware of the fact that we live in a pluralist society where various religious groups have differing beliefs about the morality of artificial contraception. But freedom of religion means more than just the freedom to believe. It also means the freedom to act or not to act according to what one believes. Hence, the state should not prevent people from practicing responsible parenthood according to their religious belief nor may churchmen compel President Aquino, by whatever means, to prevent people from acting according to their religious belief. As the “Compendium on the Social Teaching of the Catholic Church” says, “Because of its historical and cultural ties to a nation, a religious community might be given special recognition on the part of the State. Such recognition must in no way create discrimination within the civil or social order for other religious groups” and “Those responsible for government are required to interpret the common good of their country not only according to the guidelines of the majority but also according to the effective good of all the members of the community, including the minority.”

Third, I am dismayed by preachers telling parishioners that support for the RH Bill ipso facto is a serious sin or merits excommunication! I find this to be irresponsible.

Fourth, I have never held that the RH Bill is perfect. But if we have to have an RH law, I intend to contribute to its improvement as much as I can. Because of this, I and a number of my colleagues have offered ways of improving it and specifying areas that can be the subject of intelligent discussion. (Yes, there are intelligent people in our country.) For that purpose we jointly prepared and I published in my column what we called “talking points” on the bill.

Fifth, specifically I advocate removal of the provision on mandatory sexual education in public schools without the consent of parents. (I assume that those who send their children to Catholic schools accept the program of Catholic schools on the subject.) My reason for requiring the consent of parents is, among others, the constitutional provision which recognizes the sanctity of the human family and “the natural and primary right of parents in the rearing of the youth for civic efficiency and the development of moral character.” (Article II, Section 12)

Sixth, I am pleased that the bill reiterates the prohibition of abortion as an assault against the right to life. Abortifacient pills and devices, if there are any in the market, should be banned by the Food and Drug Administration. But whether or not there are such is a question of scientific fact of which I am no judge.

Seventh, I hold that there already is abortion any time a fertilized ovum is expelled. The Constitution commands that the life of the unborn be protected “from conception.” For me this means that sacred life begins at fertilization and not at implantation.

Eighth, it has already been pointed out that the obligation of employers with regard to the sexual and reproductive health of employees is already dealt with in the Labor Code. If the provision needs improvement or nuancing, let it be done through an examination of the Labor Code provision.

Ninth, there are many valuable points in the bill’s Declaration of Policy and Guiding Principles which can serve the welfare of the nation and especially of poor women who cannot afford the cost of medical service. There are specific provisions which give substance to these good points. They should be saved.

Tenth, I hold that public money may be spent for the promotion of reproductive health in ways that do not violate the Constitution. Public money is neither Catholic, nor Protestant, nor Muslim or what have you and may be appropriated by Congress for the public good without violating the Constitution.

Eleventh, I leave the debate on population control to sociologists.

Finally, I am happy that the CBCP has disowned the self-destructive views of some clerics.

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Smuggling is ‘embedded’ in Customs, says group

Philippine Daily Inquirer

First Posted 20:58:00 05/10/2011

DAVAO CITY – The recent discovery of hot cars and big bikes in Cagayan de Oro City and Bukidnon exposed a system of corruption embedded at the Bureau of Customs that can be stopped through a proposal made to President Benigno Aquino III by an anticorruption group here.

For Benjamin Lizada, lead convenor of the People Power Volunteers for Reform-Davao City, the case in Bukidnon and Cagayan de Oro City is reflective of unabated smuggling in the entire country.

“I hope we can all help in solving the smuggling problem in our country. It is very easy to solve,” Lizada told the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

His group sent a letter on March 6 to President Aquino proposing the revival of Designated Examination Areas (DEA) outside customs zone as an effective way to fight smuggling.

The letter was also signed by Fathers Archimedes Lachica and Albert Alejo, of the anti-corruption movement Ehem, and Ednar Dayanghirang, a member of the government peace panel negotiating with the National Democratic Front.

Successful experiment

The DEA experiment, said Lizada, had proven to be successful in Davao City. A few months after the customs bureau agreed on Jan. 9, 2009, to set up a DEA in the city, Lizada said 40 vans of smuggled rice had been discovered and reported.

But instead of investigating the smuggling, Lizada said customs officials worked to remove the DEA from the Davao port.

“It has been done and the solution is very simple,” said the letter of Lizada’s group to Mr. Aquino. “But for it to work, you have to give the order to revive it yourself. Do not leave it to the BOC,” the letter read.

It said Lizada’s group had approached several officials, including Budget Secretary Florencio Abad Jr. and Social Welfare Secretary Dinky Soliman, “but it seems the request for an investigation gets lost in the paper work.”

Lizada’s group also recommended that reports of anomalies be sent directly to the customs main office in Manila with copies furnished local customs offices and accredited watchdog groups.

It said the DEA operator should be from the area where the port is to prevent a monopoly of DEA operations by a single individual. It also recommended that a local citizens’ group be officially designated as watchdog in areas where smuggling is rampant.

Abolished by customs

Davao’s DEA, which was placed inside the property of businessman Rodolfo Reta, was stripped of its functions in February last year by former Davao customs chief Anju Castigador. It was Reta who reported the smuggling of 40 container vans of rice that were declared as construction materials when it entered the Davao port.

It was not the first time that Reta reported smuggling, but instead of acting on his reports, Castigador terminated the 25-year contract to operate the DEA.

“You will hear a lot of derogatory stories about the Davao City DEA operator,” said Lizada.

“Already he is being linked to certain politicians to discredit him. But the truth is as DEA operator, he fulfilled his functions...Because of this, the previous administration canceled the agreement,” Lizada said.